Birds & Bubbles

Tuesday, January 13, 2015 at 01:19PM

Tuesday, January 13, 2015 at 01:19PM  It’s not exactly an obvious combination, is it? Fried chicken and champagne?

It’s not exactly an obvious combination, is it? Fried chicken and champagne?

Obvious or not, that’s the value proposition at Birds & Bubbles, the peculiar and yet oddly compelling restaurant from the home cook turned chef, Sarah Simmons.

The restaurant is on an uncharming Lower East Side street, in a narrow subterranean space that was previously an appropriately named restaurant called Grotto. The hours suit the clubby neighborhood nearby, with a 2am closing time Thursdays through Saturdays.

The backstory in brief: Simmons was a retail strategist who started a supper club in her apartment, cooking the soul food she’d grown up with in South Carolina. After winning Food & Wine’s Home Cook Superstar award in 2010, she started City Grit, a so-called “culinary salon,” where guests buy tickets to dinner. Originally an extension of Simmons’ in-home supper club, nowadays she cooks there only occasionally: visiting chefs prepare most of the meals.

Simmons knows her stuff. I liked the food at Birds & Bubbles a lot. It’s Southern comfort cuisine, and does not blaze any culinary trails. But the chicken’s really enjoyable, the bread and side dishes well above anything you get at the average poultry joint.

Simmons knows her stuff. I liked the food at Birds & Bubbles a lot. It’s Southern comfort cuisine, and does not blaze any culinary trails. But the chicken’s really enjoyable, the bread and side dishes well above anything you get at the average poultry joint.

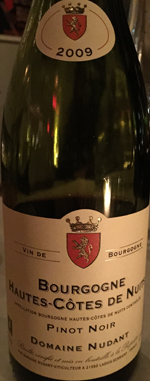

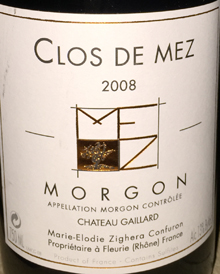

Unfortunately, the wine menu looks like it parachuted in from another planet, or at least another restaurant. It consists mostly of champagnes over $100 a bottle, with only a few sparkling wines in the $45–65 range and a handful of cheap, uninteresting still wines you probably don’t want.

If you order cocktails or bubbly by the glass, as we did, the costs quickly mount up: dinner for three was over $200, including tax and tip. That’s an awful lot for a meal whose centerpiece is fried chicken served in a stainless steel bucket. The food menu is inexpensive, with salads, appetizers and soups $5–13, mains $17–24, and side dishes $9.

For a group, the Winner, Winner, Chicken Dinner ($55), which we ordered, offers a good cross-section of the menu: a whole chicken, a bread basket ($12 if purchased à la carte), and your choice of three side dishes. You don’t have to eat chicken: there’s a crawfish étouffée, shrimp & grits, a steak, and so forth. But you don’t order the salmon at Peter Luger, do you?